|

Bread and Circuses

Join Date: Apr 2009

Location: Jewed Faggot States of ApemuriKa

Posts: 6,666

|

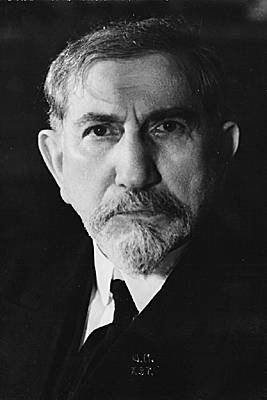

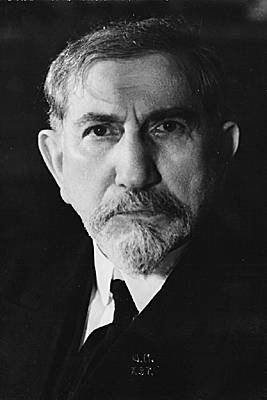

Charles Maurras

Charles Maurras

Quote:

|

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (French: [ʃaʁl moʁas]; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, poet, and critic. He was a leader and principal thinker of Action Française, a political movement that was monarchist, anti-parliamentarist, and counter-revolutionary. Maurras' ideas greatly influenced National Catholicism and "nationalisme intégral". A major tenet of integral nationalism was put forth by Maurras as "a true nationalist places his country above everything". A political theorist, a major intellectual influence in early 20th-century Europe, his views anticipated some of the ideas of fascism.

|

Quote:

Charles Maurras, in full Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (born April 20, 1868, Martigues, France—died November 16, 1952, Tours), French writer and political theorist, a major intellectual influence in early 20th-century Europe whose “integral nationalism” anticipated some of the ideas of fascism.

Maurras was born of a Royalist and Roman Catholic family. In 1880, while he was engaged in studies in the Collège de Sacré-Coeur at Aix-en-Provence, he contracted an illness that left him permanently deaf, and he took refuge in books. Having lost the religious faith of his parents, he built his own conception of the world, aided by the great poets from Homer to Frédéric Mistral, as well as the Greek and Roman philosophers.

In 1891, soon after his arrival in Paris, Maurras founded, with Jean Moréas, a group of young poets opposed to the Symbolists and later known as the école romane. The group favoured classical restraint and clarity over what they considered to be the vague, emotional character of Symbolist work. After the “Dreyfus affair,” which polarized French opinion of the right and left, Maurras became an ardent monarchist. In June 1899 he was one of the founders of L’Action française, a review devoted to integral nationalism, which emphasized the supremacy of the state and the national interests of France; promoted the notion of a national community based on “blood and soil”; and opposed the French Revolutionary ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité (“liberty,” “equality,” and “fraternity”). In 1908, with the help of Léon Daudet, the review became a daily newspaper, the organ of the Royalist Party. Over a period of 40 years, its causes were often reinforced by public demonstrations and riots, spectacular lawsuits and trials.

Maurras also acquired a reputation as the author of Le Chemin de paradis (1895), philosophical short stories; Anthinea (1900), travel essays chiefly on Greece; and Les Amants de Venise (1900), dealing with the love affair of George Sand and Alfred de Musset. Enquête sur la monarchie (1900; “Enquiry Concerning Monarchy”) and L’Avenir de l’intelligence (1905; “The Future of Intelligence”) give a comprehensive view of his political ideas. After World War I, he was still admired in literary quarters as the poet of La Musique intérieure (1925), the critic of Barbarie et poésie (1925), and the memorialist of Au signe de Flore (1931). But he lost some of his political influence when on December 29, 1926, the Roman Catholic Church placed some of his books and L’Action française on the Index, thus depriving him of many sympathizers among the French clergy. The reason given for the ban was the movement’s subordination of religion to politics.

Maurras was received into the Académie Française in 1938. During the German occupation in World War II, he became a strong supporter of the Pétain government. He was arrested in September 1944 and the following January was sentenced to life imprisonment and excluded from the Académie. In 1952 he was released on grounds of health from the prison at Clairvaux and entered the St. Symphorien clinic in Tours. Reconciled with the Roman Catholic Church, he produced the poems of La Balance intérieure (1952) and a book on Pope Pius X, Le Bienheureux Pie X, sauveur de la France (1953).

|

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/...harles-Maurras

The Dreyfus Affair

An Affair of State

By Charles Maurras

Quote:

Source: Charles Maurras, Au Signe de Flore. Paris, Grasset, 1933;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitchell Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2007.

No figure on the French far-right was as influential as Charles Maurras. His organization and newspaper, “L’Action Francaise,” were the focal point for an odious mix of royalism and anti-Semitism that was to bear fruit in every fascist and collaborationist group before and during World War II.

An affair of state broke out in this country that had almost no state.

For the crime of treason the brevet Captain of the General Staff, Alfred Dreyfus had been condemned to perpetual detention and sent to a penal colony. He had been there for two years. Around the middle of 1897 a rumor spread around Paris: that officer had been condemned as Jew; the bordereau that he was accused of having written had been written by another, and the Jews, proof of his innocence in hand, were going to move heaven and earth to prove it. The designated apologist was another Jew named Bernard Lazare.

This Lazare had just written a book on “Anti-Semitism, its History and its Causes,” whose argument rested on two quite luminous principles, for it reconciled, while at the same time explaining, Marx and Rothschild, Bleichroeder and Lasalle: The Jew is a revolutionary agent; the Jew is a conservative as regards himself.

It would be difficult to find a better definition.

The French were warned.

The following autumn, after two pamphlets by Lazare had prepared certain strata of opinion, the campaign begun in the cellars of parliament extended to the major press. In just a few days it became so lively that the object of it was nearly covered over by the passions he excited. The degraded captain disappeared beneath the agitation provoked by his image. The Dreyfus Affair became simply the Affair.

Where was the Affair going to lead a state so weak, a nation so divided, an army so exposed?

The Minister of War affirmed at the tribune that Dreyfus had been justly and regularly condemned and, his dual word of honor thus produced, he found neither in the laws nor in himself the means to effectively put down a slanderous and anarchic defamation. In the half measures attempted one after the other we can see the fear of the great remedies that alone would have worked. Opinion was divided into two camps: one cried out “Truth! Justice!” while producing only fables and insults; the other “Fatherland, Honor, Flag” without proposing anything practical or rational.

Nevertheless, two or three newspapers, expressly founded for this purpose qualified the army and its chiefs in a tone and in language that troubled the French of 1897. When seeing soldiers gathered at the gates of barracks to read in l’Aurore or La Petite République the filthy litany of invective against the braided and the saber draggers you had the right to ask if we weren’t headed for another Commune. More simply, it was the butchery of 1914 that was being prepared.

Since 1870, despite or because of Boulangisme, the French masses had remained attached to their army. All the maneuvers of anti-military propaganda had failed, for the country had maintained its feeling for the need for a permanent defense against Germany. On this we were united...

Anti-patriotism remained circumscribed within refined philosophical circles. Despite Gourmont, who declared himself unable to sacrifice for the re-taking of Alsace either his right hand, which held a sacred quill, or the little finger of his left, which served to shake off the ash at the end of his cigarette, we continued “to be hypnotized by the blue line of the Vosges,” despite the counsels of Jules Ferry. Bétheny’s review had inspired enthusiasm in the country, and no one doubted that the prompt re-raking of Strasbourg and Metz was the common objective of M. Felix Faure and Tsar Nicholas. The army credits were always voted unanimously, and unwavering esteem was accorded to all its chiefs.

Opinion was thus still healthy; few Frenchmen imagined what a prodigious about face the spirit of public without teachers or chiefs was exposed to, or whose teachers and chiefs lacked principles, influence and activity. At the first lightning bolt of the Dreyfus Affair the old acquired knowledge of tradition and custom, all our remnants of patriotic affection, of chauvinist pride seemed to fall like rubble, torn apart, razed, carted away. We could get ourselves back in hand, but the first minute had put all in question.

Paris gazed at itself. The Jewish salons were its master. The newspapers it opened were Jewish newspapers. We though that Jewry only had a hold on money. Money had delivered everything over to it: an important sector of the university, an equivalent sector of the judicial administration, a lesser but still appreciable sector of the army, of the highest reaches of the army. At the General Staff, at the intelligence service, the Jews had their man, Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart, quickly unmasked but so well placed that he was able to do all.

What a singular hour! The various renegades, public or secret, of the army and the fatherland could follow with their worried half-smile the sordid parade of defamations, slanders, outrages against all they claimed to still serve and respect. They could hardly have dared this, but they had calculated the consequences and the profits. As for the foreign minority though whom the new morality was constituted, it didn’t hide either its contempt for its elders, the passions of its aesthetic anarchism, or its ambition to tear everything down. A Jewish lady asked: “Really, they always say that we should never touch the army. Why handle it more gently than anything else? I just don’t understand.” It had been understood up till then: the men who bore the responsibility for the life or the death of millions of others should have a corresponding authority. The ferocious folly with which such clear views could be either transgressed or neglected caused in us our first shivers...

I don’t want to go into the debate on innocence or guilt. My first and last opinion on this was that if by chance Dreyfus was innocent he should be named Maréchal of France, but we should execute a dozen of his principal defenders for the triple harm they caused France, peace, and reason...

What was the origin of the political machination? It was complex, and the internal and external agents were quite varied. If Jewish pride, the Jewish spirit of domination and anarchy operated on the first line, they were very effectively served by the old republican doctrine. The Panama scandals had chased from power an old republican party that was burning to return. The Affair gave it an occasion for revenge, and its hostility towards the military sprit, its hatred for tribunals of exception found themselves stimulated by the alimentary interest to re-conquer the official posts to which rallied Catholics were already flowing, who dreamed of being associated with the government and administration of M. Meline. They counted on eliminating the newcomers and they succeeded in this by setting the republic in solidarity with the Jewish mob and the campaigns against the army. How, however much he had rallied to them, could a former officer like M. de Mun put up with so many insults to the flag? In his own words he classified himself a bad republican.

Outside of France it was probably not Germany that at first favored the agitation of the Dreyfuses. In 1897 the relations between the two countries were almost good. Since Kiel (1895) the Russian alliance had worked at a rapprochement between us and Berlin. But neither rapprochements, nor alliances of state prevent armies from spying on each other: Russia surely spied on us! Germany did the same.

Its first impulse was not to take joy in the Affair or to exploit it against us. Either it didn’t at first see the fortunate consequences for it, or its amour-propre suffered upon seeing itself taken and compromised in the person of its ambassador and its military attaché. Germany attempted at first to put a halt to it all with saber rattling. The first encouragement for the Dreyfusards, perhaps even the first inspiration, and certainly the money, came to them from England. This is because at the time England was in the position of a half-enemy: worried by our colonial policies it felt itself targeted by the Marchand mission which, having left the mouth of the Congo in July 1896, was to reach Fachoda at the end of the summer of ‘98, at the height of the Dreyfusian crisis. Everything happened as if, watch in hand, the London government had prepared and machinated this coincidence of our success in Africa and our Parisian impotence, which gave entire satisfaction to the English.

Let us render this justice to the men of Wilhelm II: they were able to quickly see what advantage they could obtain from out civil struggles, not only for the unhindered progress of their empire, but for our enfeebling; and we can establish with certainty that from 1898-1912 they never ceased profiting from our internal embarrassments and our disarmament issuing from the Dreyfus Affair....

Whenever that fable of the victim of a judicial error was again flung at me with tremolos that still sicken me I pictured in thought a battlefield, doubtless less spacious and terrible than that which the greatest of wars was to arrange. But even so, as well as I could imagine, I saw the funereal pile of those beautiful children of France “laying cold and bloody on their poorly defended land” because the oriental mob, having overturned the ramparts and smashed the arms, they had been forced to oppose their bare breasts to the artillery. This million and a half dead and dying constitutes quite a charnel house. Those who built or enlarged it through foolish imprudence have not yet repented enough to inspire pity. As for those who coldly, by policy or fanaticism, had constructed this bloody mystification, their band will never cease receiving my malediction.

|

http://www.marxists.org/history/fran...ir/maurras.htm

Charles Maurras on the French Revolution

Quote:

A classical scholar and militant atheist and anti–Semite, Charles Maurras (1868–1952) became involved in politics during the Dreyfus Affair (1893–1906) when he founded a group known as Action Française. He believed that as a result of the Revolution, France had become dominated by outside influences, namely, Protestants, Freemasons, and especially Jews. He hoped to destroy these influences and return France to its traditional institutions, particularly the monarchy and Catholicism. Maurras and his movement embittered numerous groups and contributed to the development of attitudes and positions that would become identified with fascism between the two World Wars. Here he gives his thoughts on the French Revolution.

Nature and Reason

The sovereign freedom of a state makes it externally independent of its neighbors, but internally renders it subject to the disciplines of strength, fruitful endeavor, justice and peace. The freedom of the different associations, institutions, and groups of which it is composed consists in remaining in control of their own rules of conduct: it cannot mean the freedom to disintegrate in internal strife. Finally the freedom of the citizens themselves, according to their different roles and stations in life, is but a proposition to each that he should pursue a mode of life which is appropriate to what he must do, and wishes to do. Freedom cannot authorize them to break ranks in disorder, it is the binding force against death, it is the defensive force against division.

In contrast, the political freedom of revolutionary doctrine utters without distinction one single appeal for the general liberation of every section of society, supposedly all equal, states, enterprises, persons, entirely without taking account of their different functions. The level of this indeterminate freedom is pitched so low that men bear no other label but that which they share with every plant or animal: individuality. Individual liberty, social individualism, such is the vocabulary of progressive doctrine. How ironical it is. A dog, a donkey, even a blade of grass are all individuals. Naturally, the jostling throng of disorganized "individuals" will willingly accept from the revolutionary spirits its dazzling promises of power and happiness: but if the mob falls for these promises, it is the task of reason to challenge them and of experience to give them the lie. Reason foresees that the quality of life will decline when the unbridled individual is granted, under the direction of the state, his dreary freedom to think only of himself and to live only for himself. Posterity when it pays the price will declare this prediction all too well justified. In close parallel to this, the critical mind of the future will challenge the libertarian aspirations of romanticism, and literary history will see clearly the damaging effect they had upon the poet and his work: enslavement, decomposition.

Thus we find, in politics as in art, the harmony of nature and reason. Criticism and logic, history and philosophy, far from being in conflict, come to the aid of each other. We have had to dwell on this point before. Foreign influences (English mainly) at work in reverse upon the French conservative spirit, tended to represent the principles of the Revolution as an expression of the rational, and the principles of reaction as the voice of the natural world. Abstract reason had erred. Experience, with its clear view of the concrete, rectified the spirit's error, embodying thus the triumph of practical good sense (mental error being the child of pure theory!). This amounted to saying that all theories are false, all generalizations suspect. With one accord we have rejected this contradictory system and refused to dismiss all ideas simply because they are ideas. This rejection applies equally to the gratuitous notion that some special honor is due to an undefined "idealism" which admits any old system of ideas if it seems to oppose reality. In fact reality and ideas are in no sense opposite or incompatible. There are ideas which are consistent with reality and these are the true ideas. There are realities which are consistent with the noblest ideas and these we call great men, beauty, sacred things. If contradiction we must establish, it is between true ideas and false ideas, between good reality and bad reality. No man of sense will condemn revolutionary ideas merely because they are abstract or generalized. Let us throw light upon this confusion.

Politics is not morality. The science and art of the conduct of the state is not the science and art of man's own conduct. What satisfies general man, can be profoundly disagreeable for the particular state. By losing its head in these metaphysical clouds, concentrating upon these insubstantial wraiths, the Constituent Assembly managed to overlook entirely the problem it was called upon to resolve. Its mind wandered and what followed is the proof.

Furthermore, as if it were not enough for the Assembly to use a pair of scales to measure out a gallon of water, it compounded the error by using false weights. From the standpoint of reason as invoked by itself, the general ideas of the Revolution are the antithesis of truth. In drawing up the French constitution, it felt inclined to speak of an ideal and absolute type of man in Article I of the Declaration of the Rights of Man: that they be born and live free and equal before the law. "What," exclaimed Frederic Amouretti,1 "a child five minutes old is a free man!" And, of course, it logically follows from the declaration that this infant has the same freedom as its mother and father!

In exactly the same way, if the Assembly was disposed, when dealing with a tangible entity called France, to reason in terms of political society in general, it should have avoided the pitfall of holding that the social group is an "association" of individual wills whose "aim" is to "conserve" "rights" (as Article 2 has it) since society is in being before the will to associate, since man is a part of society even before he is born, and since the rights of man would in any case be inconceivable without the existence of society. Any affirmation to the contrary, belied in nature, is totally untenable in reason. Whoever drafted such articles produced a mere collection of words without having examined what they meant. There is nothing more irrational.

Nor is it rational that all men should command everyone to be sovereign: this is yet another contradiction in terms so characteristic of the pure and unadulterated irrational. It is not rational that men should meet to elect their leaders, for leaders have to command and an elected leader is little obeyed; elected authority is an instrument which bears no relation to its intended function, an instrument first ridiculous then defunct. If it is not rational, it is contradictory, that the state, founded for the purpose of building unity amongst men, unity in time which we call continuity, unity in space which we call concord, should be legally constituted by competition and discord between parties which by their very nature are divisive. All those liberal and democratic concepts, principles of the revolutionary spirit, are no more than an essay in squaring the circle.

It should not be supposed that even at the outset the needle of reason failed to pierce the skin of revolutionary principle and expose its weakness. Its first critics were not just simple practical men like Burke whose sense of politics and history had been somewhat shocked. Good critical minds, clear vigorous spirits like Rivarol2 and Maistre, found intolerable the absurd because it was absurd; in the unreason of liberal and Jacobin they foresaw disasters to come; error and catastrophe.

The catastrophes they predicted came to pass. Revolutionary legality has broken up the family, revolutionary centralism has killed community life, the elective system has bloated the state and burst it asunder. While the enfeeblement of peaceful crafts has brought about the recession of the economy; five invasions, each more severe than the last, have demonstrated, both in defeat and in victory, despite the immense sacrifices of our nation, the total inadequacy of the New Spirit and the New State.

Of the three revolutionary ideas now written up on every wall, the first, the principle of political liberty, essence of the republican system, has destroyed not only the citizen's respect for the laws of the state which he regards as the commonplace expression of a passing whim (no whim is permanent), but also and above all his respect for those other laws, profound and solemn; leges naturae, offspring of nature's union with reason, laws in which the caprices of man or the citizen count for less than nothing. Oblivious, negligent and disdainful of these natural and spiritual laws, the French state threw discretion to the winds and exposed itself to the gravest dangers and corruptions.

The second of the revolutionary ideas, the principle of equality, essence of the democratic system, handed over power to the most numerous, that is to say the most inferior elements of the nation, to the least vigorous producers, to the most voracious consumers, who do the least work and the most damage.

The Frenchman is continually discouraged, if he is enterprising, by a meddling administration legally representative of the greatest number, but finds himself, if he is meek and humdrum, in receipt of the favors with which the same administration gratefully blesses his idleness, and so he has resigned himself to being an office parasite to such an extent that the flame of French national life burnt low and almost died because individuals are not helped to become people or rather because people are dragged down to the level of a herd of individual sheep.

Finally the third revolutionary idea, the principle of fraternity, the essence of cosmopolitan brotherhood, imposed on the one hand a limitless indulgence towards all men, provided they lived far enough away from us, were unknown to us, spoke a different language, or, better still, had a skin of different color. On the other hand this splendid principle allowed us to regard anyone, be he even fellow citizen or brother, as a monster and a villain if he failed to share with us even our mildest attack of philanthropic fever. The principle of universal fraternity which was supposed to establish peace among nations, has taken that frenzy of anger and aggression built by nature into the secret mechanism of that political animal, that political carnivore rather, called man, and turned each nation upon itself, upon its own compatriots. Frenchmen have been instructed in the arts of civil war.

And that is not all. The same ideas, distributed worldwide as French merchandise to all our customers, brought great harm to them and returned with interest upon our own heads.

1Joseph-François-Frederick Amouretti (1863–1903), like Maurras a Provençal; disciple of Mistral who led a movement (Le Felibrige) for the revival of the Provençal language. His passionate provincialism influenced both Barres and Maurras. He contributed frequently to the Cocarde when it was run by Barres.

2Antoine de Rivarol (1753–1801), man of letters, journalist, and pamphleteer, famous for the saying, "Ce qui n'est pas clair n'est pas français" [If it's not clear, it's not French]. Respectfully received in England by Pitt and Burke.

Source: J.S. McClelland, ed., The French Right (From de Maistre to Maurras), trans. John Frears (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), 251–55. Copyright © 1970 by J.S. McClelland. Translations by John Frears, Eric Harber, J.S. McClelland, and R.H.L. Phillipson © 1970 by Jonathan Cape Ltd. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

|

http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/594/

|

Linear Mode

Linear Mode