|

|

|

|

#1 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

I came across this long and scholarly article in the process of finding out what a Negro cost before the War Between the States. This article allows the calculation of the cost when measured in current 2013 Jew dollars. This brought me to some staggering conclusions about modern day Negroes and Mexicans that I will post shortly. The authors allow complete posting with attribution.

Quote:

|

|

|

|

#2 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

Here is the second part of four. A poster on this forum correctly observed that Negroes are obsolete farm implements. I say that they are badly in need of recycling.

Quote:

Last edited by Donald E. Pauly; August 24th, 2013 at 10:02 PM. Reason: typo |

|

|

|

#3 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

Here is the third part. I did the best that I could on the tables without access to HTML.

Quote:

|

|

|

|

#4 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

Here is the fourth part with comments, references and contact information.

Quote:

Last edited by Donald E. Pauly; August 24th, 2013 at 10:03 PM. Reason: format |

|

|

|

#5 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

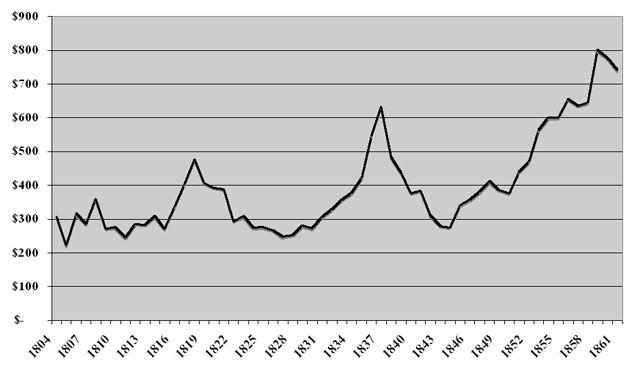

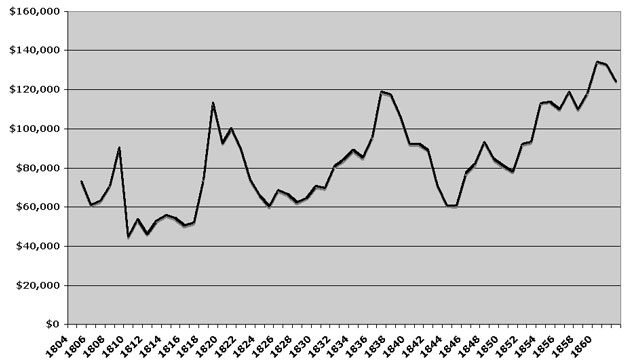

The first thing that jumps out is the the dollar was stable from 1789 to 1913 when the Jews took over the Federal reserve. Since then it has lost 99% of its value. Gold in 1860 was $20 per ounce and its real price is now about $1,600. This is an 80 to 1 reduction in the true value of the money. The various prices here can be approximated in current dollars by multiplying the old figures by 80.

An average priced Negro in 1860 cost $800. This is $64,000 now. This is the price of a used tractor. The tractor can do 100 times as much work as a Negro. It does not have to be whipped to get it to work and will not try to escape. Even if slavery was legal, you couldn't get $10 for a Negro today. These days there is no work that a Negro can do that is worth the price of the food to keep it alive. |

|

|

#6 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

I can't think of anything in history that has shown such a disastrous drop in price as a Negro. They were worth on average about $64,000 in current dollars before the War Between the States. You couldn't even get $10 for a Negro these days even if slavery was legal. The best slide rule in 1960 cost about $100 which is $3,000 now. It would still fetch $100 as a collector's item. That is only a 30:1 drop in price. The Negro has experienced an infinite drop in price. Nobody would even want one for a conversation piece.

|

|

|

#7 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

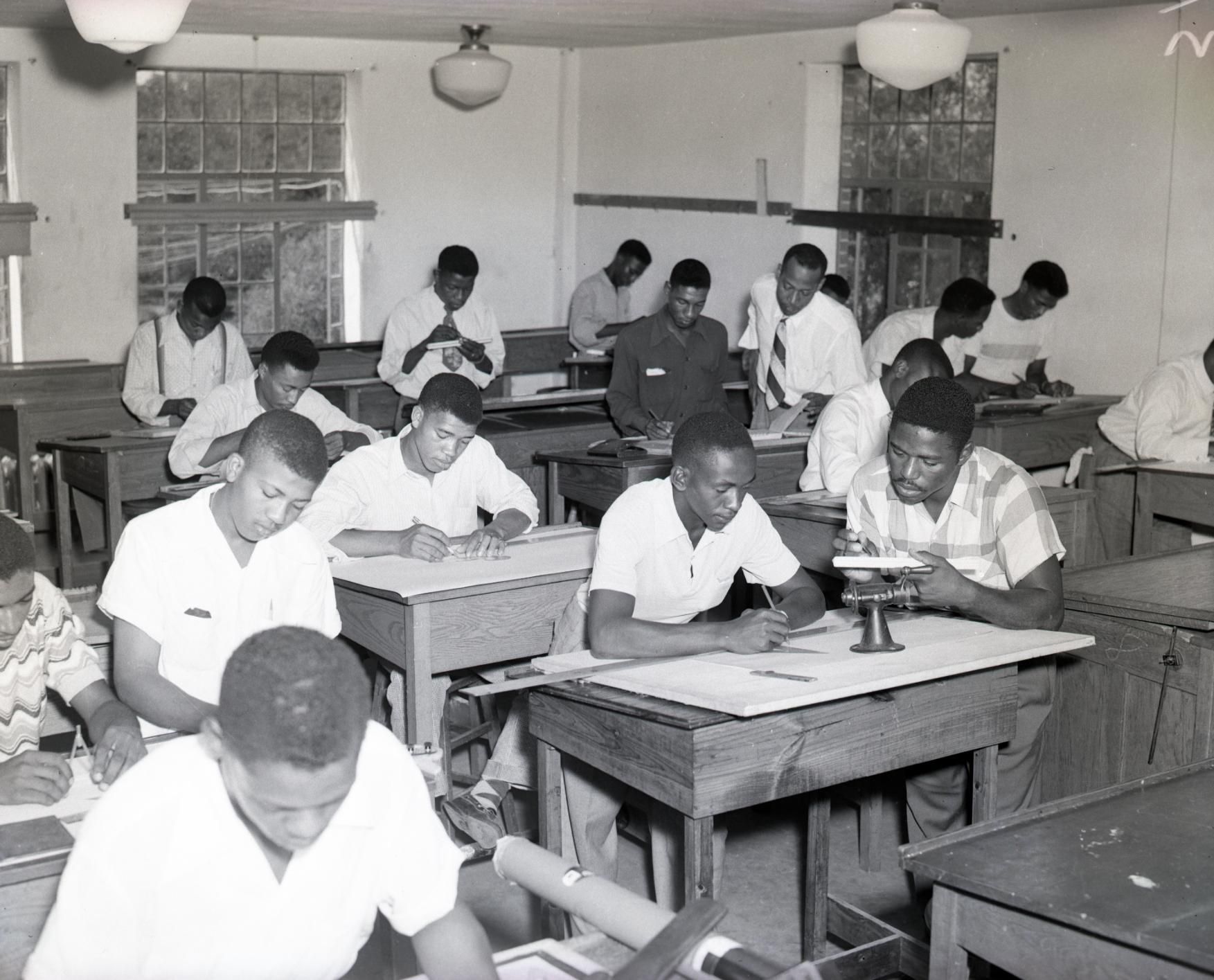

These slide rules are still worth something in this picture from 1950. The Negroes are not worth anything.

1950 African-American Students.Prarie View, TX. Texas A&M Last edited by Donald E. Pauly; August 27th, 2013 at 09:28 AM. Reason: typo |

|

|

#8 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

This video commemorates the days when Negroes were still worth something. They sang those Negro spirituals in the fields while they were picking cotton.

|

|

|

#9 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

This photo was taken in 1940 before the cotton picking machine had been invented. It was no longer legal to own Negroes but they would still work a little bit if you paid them. When the cotton picking machine was invented, the Negro market collapsed. Lyndon Johnson's so called Great Society finished the collapse. This type of Negro was once worthy $64,000 in current money!

|

|

|

#10 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

The price of Negroes which had a history of running away was much lower that that of an obedient Negro. After an escape, they typically sold at a 60% discount. It was very expensive to get them back, especially if they ran away to a free state.

Here is an example of a troublesome Negro midget who escaped when he was drunk. Because of inflation, the reward for his return would now be about $8,000 and for his arrest about $3,200. This presumably means that it would have cost $4,800 to bring this Negro back to his master. This Negro probably would have been worth around $64,000 in current money if he had never escaped. After an escape he would have been only worth $25,600. It wouldn't take very many escapes to make a Negro worth nothing. Quote:

|

|

|

|

#11 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

In these days, law enforcement was good for something besides writing speeding tickets. They returned escaped slaves to their rightful owners.

Quote:

|

|

|

|

#12 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

I finally found this on Google books. This planter figured out how to get work out of Negros after slavery became illegal.

Quote:

Last edited by Donald E. Pauly; September 5th, 2013 at 12:43 PM. Reason: typo |

|

|

|

#13 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

My buddy Calypso Louie, aka Minister Farrakhan, has some words of wisdom on slavery, Uncle Sambo and Tiger Woods. Louie doesn't like skittles.

Last edited by Donald E. Pauly; September 7th, 2013 at 03:23 PM. Reason: typo |

|

|

#14 | |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

The Council of Conservative Citizens points out that the first legal slaveholder in North America was a Negro. Prior to 1655, Negroes could only be indentured for seven years. I didn't know that Sierra Leone was formerly used for repatriating Negroes.

Quote:

|

|

|

|

#15 |

|

Banned

Join Date: Dec 2003

Location: Las Vegas

Posts: 4,130

|

For those not familiar with Pastor Manning from Harlem, here is one of his better sermons. He criticizes Negros for not doing anything in Africa until the White man colonized the continent. He points out that the White man got some work out of Negroes during slavery.

|

|

| Tags |

| inflation, negroes, slave trade, slavery |

| Share |

«

Previous Thread

|

Next Thread

»

| Thread | |

| Display Modes | |

|

|

All times are GMT -5. The time now is 04:24 AM.

Page generated in 0.32867 seconds.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode