|

|

|

|

#1 |

|

Banned

|

|

|

|

#2 |

|

Banned

|

His final broadcast on April 30, 1945

|

|

|

#4 |

|

Banned

|

http://www.barnesreview.org/html/joyce.html

The Martyrdom of William Joyce By Michael Walsh William Joyce is too often remembered as “Lord Haw-Haw,” a name that seems like a joke—and is. However, those who really know who this man was will recognize that he was an exceptional individual, who suffered martyrdom for his pro-Western beliefs. Intellectually gifted William Joyce had a family tree to be proud of. Theirs was a family whose merits had given an entire region of Galway, Ireland their name: “Joyces’ Country.” Their roots traced back to William the Conqueror’s colonization of medieval England and the later crusades. Among Joyce’s ancestors were three archbishops, three founders of the Domin ican College at Louvain, several mayors of Galway, an historian, a 19th-century poet-physician, an American revivalist preacher, and the noted author and poet James Joyce. William’s father, Michael Joyce, as a 20-year-old British citizen (Ireland was then ruled from Westminster), had emigrated to the United States in 1888. Four years later he renounced his British citizenship and became an American citizen. He was very successful in his trade and returned to Ireland in 1909 to live in comfort. Fiercely loyal to the crown and proudly pro-British, the Galway County inspector of police was unstinting in his praise of Michael Joyce, who now, through lapse, considered he was again a British citizen. Not so, the chief constable of Lancashire informed him. He and his wife Gertrude were formally cautioned against the provisions of the Aliens Restriction Order (July 8, 1917). Michael and his wife were now in no doubt as to their, and their son’s, nationality: They were citizens of the United States of America. At the conclusion of the Anglo-Irish Treaty (December 8, 1921) when a portion (26 counties) of Erin gained independence, Michael Joyce, no doubt due to his anti-Republican sympathies, re moved himself to England to dedicate himself to king and empire. William was then 15. There was never any doubt as to his son’s similar loyalty to the crown, an excess of which caused him to lie about his age when enrolling in the Regular Army at 16. He was ejected after four months service, when his true age was revealed. The young Joyce joined the Officer Training Corp. It was through the OTC college system that the dedicated and highly cerebral student acquired BAs in Latin, French, English and history. Later on, in 1927, he obtained first-class honors in English. In terms of his academic brilliance Joyce’s achievements have never been bettered. His close friend, John Angus Mac Nab, described how Joyce could quote Virgil and Horace freely. Besides being able to speak German, he spoke French fairly well and some Italian. He was not only gifted in mathematics but had a flair for teaching it. He was also widely read in history, philosophy, theology, psychology, theoretical phys ics and chemistry, economics, law, medicine, anatomy and physiology. He played the piano by ear. This was a period of international up heaval and uncertainty. The “Russian” Revolution and bitter civil war were now over. Events had delivered that great nation to the tyranny of international Jew ish revolutionaries. Bankers such as New York-based Kuhn, Loeb and Co., who shared their ilk and presumably the ensuing opportunity for profit, had financed these revolutionaries. Europe was horrified at what appeared to be the relentless flames of revolution licking at their own shores. Winston Churchill was on record as saying: It may well be that this same astounding race may at the present time be in the actual process of providing another system of morals and philosophy, as malevolent as Christianity was benevolent, which if not arrested, would shatter irretrievably all that Christianity has rendered possible . . . at last this band of extraordinary personalities from the underworld of the great cities of Europe and America have gripped the Russian people by the hair of their heads and have become practically the undisputed masters of that enormous empire.1 Against this background, the young Joyce, on December 6, 1923, joined Miss Linton-Orman’s British Fascisti Limited, an organization set up to counter Red revolutionary activity. Joyce was soon to come face to face with Red revolutionaries. During an election meeting, a communist thug leaped on the 18-year-old acti vist’s back and with an open razor slashed him from mouth to ear. It was a scar that Joyce carried with him to the gallows. Dur ing this period of international upheaval, membership in a fascist organization and the defense of the British empire were one and the same thing. Indeed it was so in Germany, Italy and many other European nations then battling against the communist struggle for world domination. The political event Joyce was defending when attacked was an election meeting for the Unionist Parliamentary candidate, Jack Lazarus. In 1933, The Financial Times brought out a special eight-page supplement under the caption: “The Renaissance of Italy: Fascism’s Gift of Order and Progress.” As late as November 11, 1938, Winston Chur chill opined: Of Italian Fascism, Italy has shown that there is a way of fighting the subversive forces which can rally the masses of the people, properly led, to value and wish to defend the honor and stability of civilized society. Hereafter no great nation will be unprovided with an ultimate means of protection against the cancerous growth of Bolshevism.2 Only later would the defeated British empire genuflect to the triumphant airs of The Internationale. Joyce, reluctant to commit himself to existing anti-communist organizations, eventually opted for Oswald Mosley’s newly formed British Union of Fascists (BUF). He remained skeptical, however, of Benito Mussolini.3 His skepticism was due to the Italian leader’s apparent lack of concern at the threat posed by organized world Zionism. On the other hand, he had great admiration for Ger many’s recently elected leader, Adolf Hitler. Fired by the prospect of accompanying BUF leader Oswald Mosley to Germany with the possible opportunity of meeting the Führer, the young Joyce was to unwittingly sign his own death warrant. Real izing that as an American citizen it would be impossible to obtain a British passport, he lied about his place of birth to obtain the document. Obviously such a document was invalid, but Britain’s judiciary would later be happy to make an exception to the rule if it would provide opportunity for a legalized hanging. Ironically the proposed trip to Germany never did take place. An excellent speaker, Joyce often deputized for Oswald Mosley. He regularly addressed large audiences including a major fascist rally in Liverpool on November 26, 1933, attended by an esti mated 10,000 fascists. Of him A.K. Chesterton wrote: Joyce, brilliant writer, speaker, and exponent of policy, has addressed hundreds of meetings, always at his best, always revealing the iron spirit of fascism in his refusal to be intimidated by violent opposition. John Beckett, the former Labour member of Parliament on attending a meeting addressed by Joyce said: “Within 10 minutes of this 28-year-old youngster taking the platform, I knew that here was one of the dozen finest orators in the country.” Cecil Roberts, who heard Joyce at a political dinner in London’s Park Lane Hotel described the event years later: Thin, pale, intense, he had not been speaking many minutes before we were electrified by this man. I have been a connoisseur of speech-making for a quarter of a century, but never before, in any country, had I met a personality so terrifying in its dynamic force, so vituperative, so vitriolic. During this period Oswald Mosley was speaking at the largest political rallies ever held in Britain. “We know that England is crying for a leader,” Joyce told a Brighton audience in 1934, “and that leader has emerged in the person of the greatest Eng lishman I have ever known, Sir Os wald Mosley.” Joyce’s political sympathies however were unambiguously in favor of national socialism, and by 1936 he had coined the slogan: “If you love your country you are a national[ist]. If you love her people you are a socialist. Therefore, be a national socialist.” He was equally uncompromising on the Jewish question. Then as now, it was usual for Jewish financial interests to buy a country by purchasing the party in power. In the summer of 1934 the BUF was offered 300,000 British pounds by a Jewish businessman prominent in the tobacco trade. It was sufficient to finance the BUF for two years. Without consulting his party’s lead er, Joyce rejected the offer “with an impolite message.” Joyce, if nothing else, was an in domitable champion of the working class, for whom all his efforts were directed. It was hardly surprising that he was as consistently scathing of capitalists and communists; not to mention the decadent English bootlickers, whom he described as “the parasites of Mayfair.” Joyce, by then divorced, knew one other great passion, his love for fellow party worker Margaret Cairns White. Upon the announcement of their engagement, a mutual friend said to her: “Well, I do hope you will be happy, but it may be uncomfortable being married to a genius. And William is a genius, you know.” By 1937 the English establishment’s enthusiasm for fascism had waned. The Fleet Street-based propaganda machine backed by Jewish interests was in its ascendancy. The success of National Social ist Germany and Italian Fascism, rather than being seen as a template for Euro pean solidarity and revival, was now seen as a threat to British interests, the establishment and its aristocracy. Sim plistically there were more readers of Fleet Street’s poisonous press than there were readers of the British Union of Fascist’s tabloid, The Fascist. The BBC, then as now, had always leaned toward Marxism. Riding on the back of organized anti-fascist propaganda and Red violence the government banned the wearing of political uniforms and torch-light processions. Their further tightening up of the Public Order Act hit the fascist movement hard—as intended. As the police turned a blind eye to Red riots, the owners of public halls, most of them Labour authority controlled, denied venues to the fascists. Their presses were seized and their members intimidated and harassed. The war clouds were now looming and the British fascists’ last chance to form peaceful alliance with burgeoning racial-nationalism in Europe was now fading fast. There would be no more elections until 1945. (Britain in essence was an elected dictatorship from 1937 to 1940, a parliamentary dictatorship from 1940 to 1945.) On the retreat and burdened with unsustainable overheads, the BUF staff was reduced by 80 percent. Within a month of his wedding to his Maria Callas look-alike bride, Joyce was unemployed. His enforced redundancy owed much to his disenchantment with Mosley. Joyce was intolerant of weakness exemplified by Mosley’s concessions to the then government. Subsequently Joyce, Beckett and Mac Nab set up the National Socialist League, which dismissed copying the Ger man pattern. For Joyce knew the German leader disdained imitation: His way is for Germany, ours is for Britain. Let us tread our paths with mu tual respect, which is rarely in creased by borrowing. Nationalism stands for the nation and socialism for the people. Unless the people are identical with the nation, all politics and all statecraft are a waste of time. A people without a nation are a helpless flock or, like the Jews, a perpetual nuisance; a nation without people is an abstract nothing or a historical ghost. By studying these words carefully, one can perceive why Britons today, deprived of their nationhood through open-door immigration and foreign ownership, have be come a flock without a shepherd and in many respects, especially abroad, a perpetual nuisance. By now the war clouds were darkening, leaving Joyce on the horns of a dilemma. He could not support a war arranged by corrupt politicians acting on behalf of international finance. Yet evasion of national service was unthinkable. As things turned out, there was no dilemma at all. Joyce and his wife Margaret were already marked down for arrest and detention for the duration of the coming war. In fact, many people were sentenced to long terms in prison merely for peaceful activities aimed at stopping England’s war against Germany. One such was Anna Wolkoff, the daughter of an admiral in the Russian Imperial Navy. On November 7, 1940, Judge Justice Tucker sentenced her to 10 years imprisonment. The same judge five years later would try Joyce at the Old Bailey. At the Wolkoff trial he described the absent Joyce as a traitor—a well-publicized remark that should have eliminated him from presiding over the fugitive’s later trial. Joyce’s plan was to renew his false passport and that of Margaret. Their intention was to go to Ireland, which would resolve their dilemma. However, the Munich Agreement made their departure unnecessary, and the couple went instead to Ryde on the Isle of Wight, where Joyce experienced a “spiritual visitation” of some sort, the impact of which kept him awake and talking all night. What followed was a period of much soul-searching. Events forced the young couple to decide on Berlin as being the best option to escape an English jail. Angus MacNab had already established that both Joyce and his wife would be granted German citizenship if they chose to resettle in Germany.4 Time was fast running out. The House of Commons was being re called the following Thursday to pass all stages of the Emergency Powers (War) Act. This would effectively turn the British government into a dictatorship. Joyce was under no illusions. He and tens of thousands of others who had pursued peace with Germany would be summarily arrested and detained indefinitely without trial. He applied for the renewal of their passports. As national socialists working for peace between the two nations, there was now only one country where the Joyce’s presumed they would not be imprisoned: Germany. It was an argument strongly favored by Margaret. At about midnight on August 24, the couple’s telephone rang. It was a call from a friendly MI-5 intelligence officer, warning Joyce that he was due to be arrested under the Emergency Powers Act. He had at most two days to make good their escape. On August 26, 1939, five days before Germany retaliated against repeated Polish attacks on her borders, William and Margaret Joyce left London. Arriving in Berlin they found the city seething with defensive preparations. There the English visitors found that Christian Bauer, their contact and ticket to a new life, had exaggerated his influence and could offer little by way of assistance. In the confusion of events there was even the possibility they might be interned should Britain declare war on Germany. Disconsolate and footsore the pair tramped the streets of the German capital coming up against one obstacle after another. Finally, without work and running short of money they decided in unison to return to England. Yet again fate was against them. William had changed all of his money into Deutschmarks, a currency that was now invalid for journeys beyond Germany’s borders. British Embas sy staff were unhelpful. At Margar et’s suggestion the couple fatefully decided to stay in Berlin; a decision reinforced when next day Joyce landed a job as a part-time freelance interpreter. During the night of August 31, 1939, Poland, which, six months earlier, had invaded Czechoslo vakia and which already controversially occupied German territory looted after World War I, crossed the German border. It was a little after midnight when radio broadcasts were interrupted by an an nouncement that the small German border town of Gleiwitz had been attacked and occupied by Polish irregular formations. Within hours Germany retaliated. Two days later, a delegate of the La bour Party met with British For eign Minister Lord Halifax. “Do you still have hope?” he was asked. “If you mean hope for war,” answered Halifax, “then your hope will be fulfilled tomorrow.” “God be thanked!” replied the representative of the British Labour Party. In Germany the mood was less jubilant. The shocked population listened to their country’s leader Adolf Hitler as he addressed the Reichstag on September 1: Just as there have occurred, recently, 21 border incidents in a single night, there were 14 this night, among which three were very serious. . . . Since dawn today, we are shooting back. I desire nothing other than to be the first soldier of the German Reich. I have again put on that old coat which was the most sacred and dear to me of all. I will not take it off until victory is ours, or I shall not live to see the end. There is one word that I have never learned: capitulation. Back in London the police were raiding the Joyces’ apartment, only to find the tipped-off couple had already gone. Though free in Germany, they felt lonely, helpless and homesick. They had no ration cards; William’s meager earnings reduced them to living on acts of charity. Every apparent job opportunity turned out to be a disappointment—a vague promise and nothing more. Reduced to destitution, he was finally asked: “Have you ever thought of working for the radio?” Joyce replied that he had not, and moments later an interview was being arranged. Though desperate for competent English speakers, the Reichsrundfunks Foreign Service was not impressed with Joyce’s performance (he was suffering from a heavy cold that week), but reluctantly provided employment to the equally re luctant Joyce. Faced with possible in ternment or certain destitution, he had little choice but to accept the post offered. The rest is history. Joyce spent the rest of En gland’s war providing English-speaking listeners with the German point of view on the conflict’s unfolding events. He was one of many various nationalities carrying out the same task. The same could be said for the internationally recruited staff serving the British government through the BBC at London’s Bush House. Joyce was never the “Lord Haw-Haw” of Fleet Street mythology. He was given this nom-de-plume by Daily Express journalist Jonah Barrington, who had mistaken Joyce’s broadcast for that of Norman Baillie-Stewart, a Seaforth Highland Regi ment veteran who, like many others, had decided to fight for the triumph of Euro pean interests rather than international capitalism and communism. Much of the comment made about Joyce’s broadcasts is similarly myth. His biographer, J.A. Cole, conceded that: To this day he is quoted as having made statements he never uttered. Most of what people think they know of him is false and not fact. . . . An extraordinary viciousness has characterized much of the writing about him, but what was written in anger [about Joyce] now looks spiteful and even absurd. Claims that Joyce sneeringly provided accurate predictions that certain areas or buildings had been chosen for air strikes, were also wide of the mark. The government’s Ministry of Information, having already refuted claims that Germany had detailed topical knowledge, felt the need to issue a further statement: “It cannot be too often repeated that Haw-Haw made no such threats.” Joyce’s biographer concluded by remarking: “And the legend lives on to this day. Mention ‘Haw-Haw’ in any gathering, and out come the stories of what people heard, as they will insist, with their own ears. Joyce was a man who is remembered—for what he did not say.” William L. Shirer, the author of the notable distortion, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, who worked in Berlin with Joyce, described him as the “No. 1 personality of World War II . . . an amusing and intelligent fellow.”5 What is beyond question is that Joyce’s broadcasts, with the benefit of hindsight, seem compellingly accurate. In the first radio talk definitely established as Joyce’s, the expatriate spoke of Britain’s position in the war.6 In one broadcast he commented on the hypocrisy of England’s government “‘fighting to the last Frenchman (Pole, Belgian, Norwegian . . .’); making promises it couldn’t keep.” Ironically the facts as Joyce presented them are more in accordance with the facts than those presented by the subsequent British explanation of events. England’s pact with Poland, its reason for declaring war on Germany, was later found to be illegal. Furthermore, the British government’s promise of direct aid to Poland, 9,500 planes for instance, came to nothing, as did other promises. Likewise promises made to Norway, whose neutrality was to be desecrated by British invasion. By now the German government had documents setting out the most fulsome English promises of assistance to Holland and Belgium if their territories could be used to launch attacks on Germany. These promises were subsequently found to be similarly false. Joyce spoke passionately of the “Dunkirk debacle” of the French and the British Expeditionary Force: What was England’s contribution? An expeditionary force which carried out a glorious retreat, leaving all its equipment and arms behind, a force whose survivors ar rived back in England, as the Times admitted, “practically naked.” Whatever excuses may be found for their plight the men who made the war were reduced to boasting of a precipitous and disastrous retreat as the most glorious achievement in history. Such a claim could only besmirch the proud regimental standards inscribed with the real victories of two centuries. What the politicians regarded, or professed to regard, as a triumph, the soldiers regarded as a bloody defeat from which they were extremely fortunate enough to survive. The next test of Britain’s might was the Battle of France. All the professions of brotherly love and platonic adoration which Churchill had poured forth to the French politicians resolved themselves into 10 divisions, as compared with 85 divisions, which had been in France at the height of her struggle in the last war. As the world knows, the effect was nil; and when Reynaud telegraphed madly night and day for aircraft, he was granted nothing but evasive replies. The glorious Royal Air Force was too busy dropping bombs on fields and graveyards in Germany to have any time available for France. But after the final drama of Compiegne and the defeat and the utter collapse of the French, the heroic might of the British lion suddenly showed itself at Oran. That inspired military genius, Winston Chur chill, discovered that it was easier to bomb French ships, especially when they were not under steam, than to save the Weygand line. If it was so hard to kill Germans, why not, he reasoned, demonstrate Britain’s might by killing Frenchmen instead? They were beaten and would be less likely to resent it. Joyce in this first broadcast went on to scorn Churchill’s “cowardly” response to Germany’s success in fighting back: Churchill, the genius, has his answer ready. What is it? First, Germany’s ambulance planes are to be attacked wherever seen. They can easily be identified by the Red Cross that they bear, and they are unarmed, so the great brain conceives another possibility of victory. The fact that these planes have saved many British lives weighs as nothing in comparison with the triumph that can be achieved by shooting them down. The second part of the answer is to be found in the instructions issued to British bombers flying over Germany. In reply to the charge that these machines were dropping bombs on entirely non-military places, Mr. Churchill, with another flash of genius, replies, “Of course. The planes have to fly so high that the targets cannot be distinguished!” Otherwise, the Germans would shoot them down. In consequence of this instruction, harmless civilians have been murdered at Hanover and in other towns. The British prime minister has abandoned all pretense that these bombing operations have military objectives. The principle is, “Drop the bombs wherever you can, without being seen, and what they hit, they hit.” It is unnecessary to say that a terrible retribution will come to the people who tolerate, as their prime minister, the cowardly murderer who issues these instructions. Sufficient warnings have already been given. J.M. Spaight, CB, CBE, principal secretary to the Air Ministry, afterwards admitted Churchill’s role in flouting international law by bombing civilians: Hitler only undertook the bombing of British civilian targets reluctantly three months after the Royal Air Force had commenced bombing German civilian targets. Hitler would have been willing at any time to stop the slaughter. Hitler was genuinely anxious to reach with Britain an agreement confining the action of aircraft to battle zones.7 In a later broadcast on January 4, 1944, the 37-year-old Joyce asked: “How can the ordinary British soldier or sailor understand why he should be expected to die in 1939 or 1940 or 1941 to restore an independent Poland on the old scale, while today he must die in order that the Soviets rule Europe? Surely it must occur to him that he is the victim of false pretenses?” Speaking on April 17, 1944, he said: There are today hundreds of thousands of British soldiers who will cease to live during the attempt to invade Western Europe. They are prepared to sacrifice their lives, but for what? For their country? Demonstrably not! Britain has only the stark prospect of poverty before her. For the rights of small nations? Certainly not. What British politician wants to hear of Poland today? For what, then, are these men to die? They are to die for the Jewish policy of Stalin and Roosevelt. If there is any other purpose to their sacrifice, I challenge Mr. Churchill to tell them what it is. Perhaps it was the accuracy of Joyce’s analysis of events that would later place his head in the vengeful British noose. Part of the blackening of Joyce’s character is the claim that his speeches were universally ridiculed. In fact, his broadcasts were widely listened to in Britain and far from everyone found them as laughable as was claimed by the newspapers of the time. His biographer, J.A. Cole, describes an event at which two visitors were having afternoon tea with David Lloyd George. The statesman interrupted the conversation to switch on the radio so that the Hamburg service could be heard. The former prime minister listened attentively, and once he remarked: “The government ought to take notice of every word this man says.” Life magazine accorded Germany the lead in the radio war. The influential Amer i can magazine calculated, probably correctly, that 50 percent of the English listened to Joyce’s broadcasts from Hamburg. The manager of the East Riding Radio Relay Service complained, “We are inundated with requests for Lord Haw-Haw broadcasts, which we are not allowed to give.” As the war drew to a close several attempts were made to save Joyce and his wife from English vengeance but they came to naught. Dr. Joseph Goebbels, before his death, inquired whether a submarine could be used to take the fugitives to Galway in neutral Ireland. Though not dismissed out of hand, it was impractical, and the idea was not pursued. A further plan, to allow escape to Sweden, was blocked by the Swedes. But at that late stage an escape was unlikely to succeed anyway. Denmark was in a state of near chaos, and communist bands roamed, a law unto themselves. In fact, Joyce was not inclined to either run or to take his own life, preferring to allow fate to deal with him as it might. The couple ended their days in defeated Germany much as they had begun; as wandering victims of events. As the first rays of spring were warming the north German countryside, the couple often strolled through the pastoral landscape surrounding Flensburg, contemplating the budding birch trees. Occasionally they would come across small groups of British soldiers. It amused Joyce to banter with them, and on one occasion, a knot of soldiers enjoyed a conversation with a couple whom they thought were Herr and Frau Hansen. It was precisely because Joyce did not sound like his music hall caricature that he went unrecognized. The beginning of the end came on Monday morning, May 28. Joyce had climbed to his favorite spot, the crest of the hill overlooking Flensberg’s beautiful harbor. There, to use his own words he “seemed to have fallen into a trance-like state; and with the utmost earnestness he prayed for help and guidance.” Later, realizing that his wife would be searching for him, Joyce took one final look at his beloved harbor below before turning to search for her. Following the path down the hill the former broadcaster encountered two British army officers gathering wood. Perhaps realizing that silence would be regarded as suspicious, Joyce, speaking in French to the servicemen, said, “Here are a few more good pieces.” What ever aroused their suspicion, we may never know. Capt. Alexander Adrian Lickorish of the Reconnaissance Regiment, and Lt. Perry, an interpreter, followed and overtook the limping man. “You wouldn’t happen to be Joyce, would you?” Perry asked. The conditioned response for anyone so challenged was to do as Joyce did: Reaching into his pocket, he fingered the official document that would dispel the officer’s suspicion. Before he could present it, however, Perry drew and fired his revolver. It was never felt necessary to explain why such a standard response to a simple question should have resulted in a man being violently shot down. The bullet entered Joyce’s right thigh and then went through his left leg, causing four wounds. As he fell to the ground, he cried: “My name is Fritz Hansen.” The grim irony is that the “officer” who shot Joyce, Perry, was no Englishman, nor was he a soldier. “Perry” was not his real name; the Lieutenant was an armed German Jew serving with the British forces. The wounded fugitive was handed over to the guard commander at the frontier post, where his true identity was revealed. During the ensuing raid on the couple’s lodgings a lieutenant and a party of 10 infantrymen, two Bren gun carriers and a lorry arrested his wife, Margaret. “Your husband has been arrested,” he snapped, adding that he was to arrest everyone in the house, including the children. Joyce was held at the frontier post for several hours. Then a door was eventually flung open, and the sight of soldiers confronted Margaret as they emerged, carrying her husband on a stretcher. He looked pale. As the party passed, he looked up and waved. “Erin go bragh” (Ireland forever), she called out to him. Her claim that the occupants of their lodgings had not known their true identity brought the group’s release. On returning to their home the family discovered that it had been ransacked by the troops; even their meager food supply had been “liberated.” Joyce’s arrest and subsequent im prisonment was treated as something of a freak show for the entertainment of his captors. To one of his tormentors the wounded fugitive responded: “In civilized countries wounded men are not peep shows.” Newspaper hacks, unable to afford the slightest dignity to the captured pair referred to Margaret as “his alleged wife,” or “the woman who claims to be his wife.” The macabre death procession of British justice; a parade of grim reapers garbed in the accouterment of state legislature, now began the long march to the gallows. The subsequent trial ran its murderous course and few today question that it was a judicial lynching. Joyce was not, of course, British and much of the rest of the proceedings were equally questionable. Never from the moment of his arrest to his present predicament had Joyce ever denied his role, his purpose or his belief in national socialism. To the end he took the view that friendship with Germany being in the best interests of the English people he could not therefore be a traitor. On the contrary, those who conspired with Bolshe vism to sub vert and overrun civilization were in deed the traitors. In a letter to his friend Miss Scrimgeour he wrote: One day, I hope, it will be recognized that, whether or not I aided the king’s enemies (and who made them enemies?), I was no enemy to Britain: But I had no intention of offering any apology or excuse for my conduct, which history will surely vindicate. . . . As the days go by, it will become more and more obvious that the policy which I defended was the right one. Well aware that he was being hanged for opposing a war which cost the British army alone 350,000 dead, whilst England’s bunker-bound warmongers lined their pockets and gained their peerages through war profiteering, Joyce ended his letter: I cannot quite restrain my contempt for those who would hang me for treason. Had I robbed the public and impeded the war effort by profiteering on ammunitions, a peerage would now be within my reach if I were willing to buy it. In a later letter to the same recipient Joyce wrote: “You may be sure that the Jewish interests in this country will make every conceivable effort to liquidate me.” Whatever the rituals of the court procedure, its day-to-day events were a parody; a judicial circus for the mob who, inflamed by Fleet Street, wished nothing other than the gallows (for words he never uttered). Joyce’s fate had already been decided upon despite the illegality of the charge laid against him. Undeniably, he was an American citizen, and therefore could not be subject to England’s hastily improvised Treason Act, 1945. Joyce’s defense counsel acquitted themselves well, under the circumstances. Joyce recounted afterward how, in the cell below the court, he had discussed his prospects with his counsel. They remarked in unison that they had both been threatened with assassination if the court found in his favor and counts 1 and 2 were dismissed on the grounds that Joyce was undoubtedly an alien. The crucial legal ruling as to whether he owed allegiance to the crown had yet to come. J.A. Cole described how: . . . the sparkling display of mental agility and legal erudition fascinated him (Joyce) as lawyers argued over nationality matters of mind-numbing complexity. Rumors swept the streets and public ignorance in legal complexities caused a near riot when misinterpretation (the first two charges, the assumption that he was British, being dropped) of findings suggested that the hangman had been thwarted. Joyce, however, was convinced that a state lynching was quite certain. He was under no illusions. He was a spectator and a foil; he was lending his presence to the fabrication of the spurious legitimacy of a show trial. In the outcome, Judge Justice Tucker decided that Joyce’s passport, ob tained fraudulently on August 24, 1939, for the purpose of making his escape from England, caused the defendant to owe allegiance to the crown. No doubt the same judge would have regarded an Irish Kerry Blue to be a British bulldog had its owner falsified its Kennel Club papers. In respect of the single remaining charge, a particular broadcast deemed to be treacherous, there was considerable doubt. The prosecution’s case hung (if you will excuse the expression) on what a de tective-inspector “thought he had recognized.” In fact, the inspector’s case was afterwards undermined. But it was on this third count that Joyce was found guilty: “Assist ing the king’s enemies by a specific broadcast.” “Joyce! The sentence of the court upon you is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison and thence to a place of execution, and that you be there hanged until you are dead; and that your body be afterwards buried within the precincts of the prison in which you shall have been confined before your execution. And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.” The chaplain murmured: “Amen!” Joyce stared defiantly at Judge Tucker as he pronounced the death sentence, then turned sharply and walked as smartly from the dock as he had entered it. Joyce without precedent was denied the right to express an opinion as to why the death sentence should not be carried out. In a letter to his wife, he wrote: “I thought of interrupting the judge and demanding my undoubted right to make a reply; but my contempt for the judgment, combined with a somewhat belated respect for my own dignity, kept me silent.” Joyce afterwards reflected on the judge’s reluctance to hold his gaze as he donned the black cap and read out the sentence: It gave me no small degree of satisfaction to see that His Lordship, complete with vampire chapeau, after once meeting my eyes, read his precious sentence into his desk. Ah! My dear, those were a proud few minutes of my life. To his wife he added: Some papers, I am told, have stated that my expression was contemptuous: It probably was. But whether I bore myself becomingly is, after all, for others to judge: but I do believe that I did nothing to shame me in the eyes of my lady, and I am therefore content. Whilst the condemned’s cell in London’s grim Wandsworth Prison was being prepared, Joyce was held in a Wormwood Scrubs cell. Though his counsel began the appeal procedure, Joyce was under no illusions. “Distinguished lawyers were laying 50 to 1 on an acquittal: I was not,” he wrote. Initially the date for Joyce’s execution was set for November 23, 1945, and on the 17th of that month his wife Margaret was transferred from the Belgian jail where she was being held to Holloway Prison, the women’s jail in London. The execution date having passed due to the appeals process Joyce retracted nothing of his original statement, and he advised his wife not to amend hers: Morally, if not legally, it is highly pertinent that we firmly believed ourselves to be serving the best ultimate interests of the British people—a fact which was appreciated and respected by the best of our German chiefs. And it was always our thesis that German and British interests were, in the final analysis, not only compatible but mutually complementary. The Manchester Guardian was not alone in expressing doubt as to the legality of Joyce’s forthcoming hanging: One can say that this document, which he ought never to have possessed, has been—unless the law lords judge differently—the deciding factor in Joyce’s sentence. One would wish that he had been condemned on something more solid than a falsehood, even if it was one of his own making. . . . Even in these days of violence, killing men is not the way to root out false (unpopular) opinions. Despite the dangers of association, Joyce was far from alone in his beliefs, and he received many letters of support. He wrote: “I feel overwhelmed by the generosity of my friends and these tributes from complete strangers. I am really embarrassed.” A couple in Kensington had sent a check for 50 pounds. Typically a small Suffolk farmer contributed 10 shillings “for a very brave gentleman.” On the morning of December 18, the appeal was heard—and dismissed. The death sentence was to be carried out on January 3, 1946. On December 28, he wrote to his friend Miss Scrimgeour: I trust, like you, that the works of my hand will flourish by my death; and I know there are many who will keep my memory alive. The prayers that you and others have been saying for me have been and are a great source of strength to me, and I can tell you that I am completely at peace in my mind, fully resigned to God’s will, and I am proud of having stood by my ideals to the last. I would certainly not change places either with my liquidators, or with those who have recanted. It is precisely for my ideals that I am to be killed. It is the force of ideals that the Hebrew masters of this country fear; almost everything else can be purchased by their money: and, as with the Third Reich, what they cannot buy, they seek to destroy: but I do entertain the hope that, before the very last second, the British public will awaken and save themselves. They have not much time now. In his last letter to his wife on New Year’s Day, 1946, he wrote: As I move toward the Edge of Beyond, my confidence in the final victory increases. How it will be achieved, I know not; but I never felt less inclined to pessimism, though Europe and this country will probably have to suffer terribly before the vindication of our ideals. . . . Tonight I want to compose my thoughts finally; the atmosphere of peace is strong upon me, and I know that all is ready for the transition. Visitors besides his wife found Joyce in a spiritual sense of peace. Angus MacNab eloquently expressed his feelings with these words: In his last days, although in perfectly good health, his actual body seemed spiritualized, and without what you would call pallor, his flesh seemed to have a quasi-transparent quality. Being with him gave a sense of inward peace, like being in a quiet church. Joyce, in a letter to his wife, recalled the spiritual visitation he had experienced at Ryde just before the outbreak of England’s war: It was, in those hours, as if some shadowy foreknowledge were given to me, causing a convulsion of what you might rightly call “burning of energy.” I knew that all I had and more was required of me; and I suppose I was in an emotional state arising out of “knowledge” hidden from the conscious mind. My fear on each occasion was that you would be physically torn from me; but far stronger was the feeling that we should never be spiritually separated. Such was the esteem with which Joyce was held that on the night of his execution former teachers at Birkbeck College —who remembered their likable, hardworking, although strange, student—sent a message to the governor of Wandsworth Prison. “They recalled him as they had known him, and if it were within the rules they would like the governor to tell him that they wished him well.” It was a bitterly cold morning on Jan uary 3, 1946. In a small chapel in Galway, Ireland, mass was being said for an American citizen about to be hanged in England’s grim Wandsworth Prison. The condemned prisoner was still writing his farewell notes as the liturgy began. In the last letter that his wife would receive posthumously the condemned Amer i can wrote: I never asked you if you wanted to receive posthumous letters: The question was too delicate, even for me; but I assumed your wish. For I think you are sufficiently strong now to overcome the grief of this blow, and that your faith will triumph over tears. For my part, I want to write as long as I can and then mend the snapped cable in an eternal way. At this point his letter was interrupted by his wife’s final visit. When she had gone, he continued in a smaller, neater hand: Oh, my dear! Your visit! With no words can I express my feelings about it! I want the children to take leave of me, of course, as they will this afternoon: but now I am anxious to die. I want to die as soon as possible, because then I shall be nearer to you. With the last glimpse of you, my earthly life really finished. With you, dear, it is otherwise, because you are destined to stay for a time and will have me with you to help: I am more confident than ever that we shall be together: but, after I have seen the children, the lag-end will be of no use to me except in one way; that I can still write some lines to you. Let me tell you, though, that spiritually, an unearthly joy came upon me in the last instants of your visit. And you will know exactly why. You would not blame me for being impatient to go beyond. Still, despite my impatience, I shall be glad to talk this evening to my kind, good chaplain, who has done so much for me and who will give me communion tomorrow morning. There will be a great chorus of prayer as I pass beyond. v FOOTNOTES 1Winston Churchill. Illustrated Sunday Herald. Feb. 8, 1920. 2Witness to History, Michael Walsh. Historical Review Press, Uckfield, England. 3The Italian leader had been honored as a British knight of the bath. His knighthood was removed in 1942. 4Joyce and his wife became naturalized German citizens on September 28, 1940. 5Lord Haw-Haw and Joyce, J.A. Cole, Faber and Faber, London, 1964. 6Bremen, August 2, 1940, 22.15 BST. Repeated Zeesen, August 3, 1940. 7Advance to Barbarism, F.J.P. Veale. Mitre Press, London. 1948. (Nelson Publishing Co., U.S.A., 1953). |

|

|

#5 |

|

Ausrotter

Join Date: May 2004

Location: Walhalla

Posts: 4,018

|

From a hostile source:

Joyce always said that he would fight for Hitler, even if Hitler was fighting Britain, because Hitler was fighting the Jews and ultimately this was more important. What Hitler was doing was for Britain's good in the long run. It's worth noting that Joyce was not actually a British citizen, never had been. He was American. http://www.angelfire.com/ak2/newmanbyrne/brfasc.html

__________________

"People, look at the evidence the truth is there you just have to look for it!!!!!" - Joe Vialls Fight jewish censorship, use Aryan Wiki Watch online television without jews! |

|

|

#6 |

|

Junior Member

Join Date: Jan 2009

Posts: 14

|

I didnt realise he'd died so young. Only 41

|

|

|

#7 |

|

Banned

|

|

|

|

#8 |

|

Banned

|

BUF Anthem The lyrics are as follows: Comrades, the voices of the dead battalions, Of those who fell that Britain might be great, Join in our song, for they still march in spirit with us, And urge us on to gain the fascist state! (Repeat Last Two Lines) We're of their blood, and spirit of their spirit, Sprung from that soil for whose dear sake they bled, Against vested powers, Red Front, and massed ranks of reaction, We lead the fight for freedom and for bread! (Repeat Last Two Lines) The streets are still, the final struggle's ended; Flushed with the fight we proudly hail the dawn! See, over all the streets the fascist banners waving, Triumphant standards of our race reborn! (Repeat Last Two Lines) Last edited by Mike Jahn; March 6th, 2009 at 09:18 AM. |

|

|

#9 |

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Nov 2014

Location: UK

Posts: 1,398

|

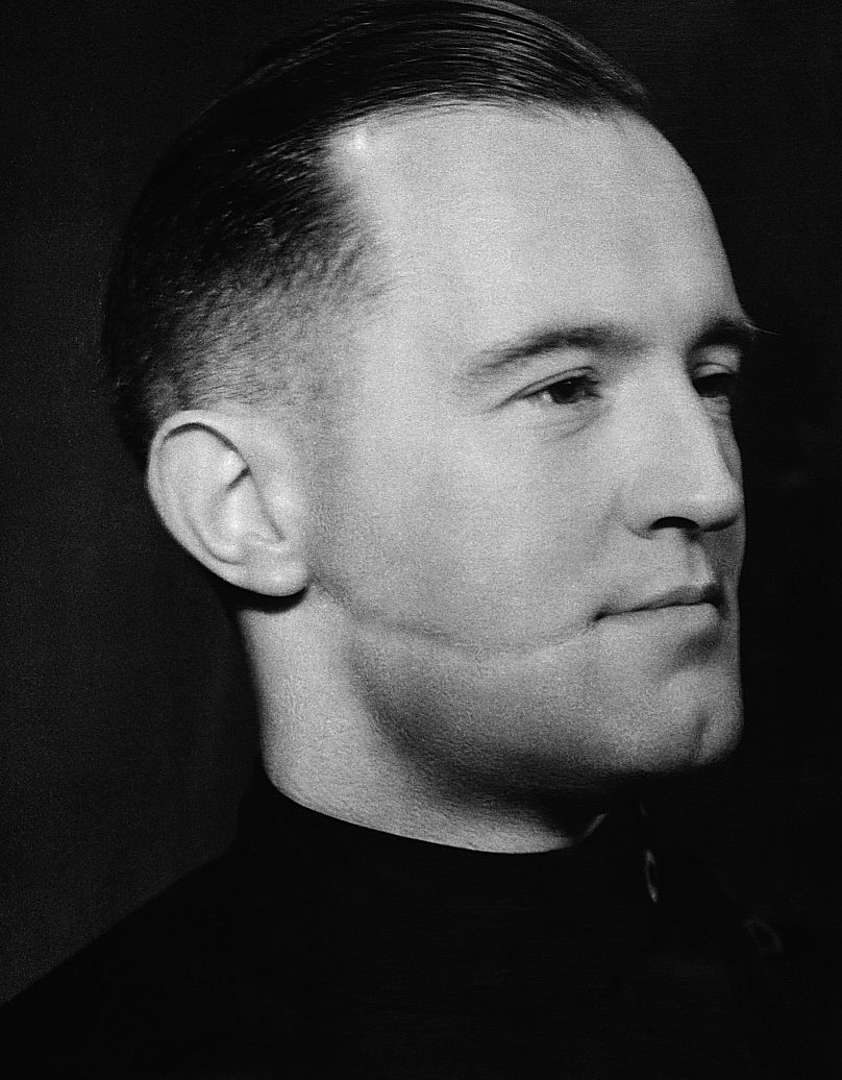

William Joyce Lord Haw Haw, WK II

William Joyce. The case of William Joyce must be one of the most famous treason trials in British legal history. Due to the legal issues involved, the case went to the House of Lords (the highest English court). Joyce did not deny that he committed the acts alleged, he denied that he had a duty of allegiance and so could not be guilty of treason. Early Life William Joyce was born on 24 April 1906 in Brooklyn, New York. He was the son of Michael and Gertrude Emily Joyce. Michael Joyce, originally came from Ireland, and became a naturalised American citizen on 25 October 1894. Three years after William's birth, the Joyce family returned to Ireland. They moved around several Irish counties during the First World War years. For immigration and registration reasons, Michael Joyce obtained a copy of his son's birth certificate which was issued in New York on 2 November 1917. In 1922 the Joyce family moved to England. Following William passing his London Matriculation examination in 1922, he applied for enrolment in the University of London Officer's Training Corps (OTC). This application was accompanied by a letter from Michael Joyce stating that "We are all British, not American citizens". In 1922 William Joyce started studying Science at Battersea Polytechnic. A year later, Joyce left his science course and stared on a English Language, Literature with history course at Birbeck college. He graduated in 1927. Following his coming-of-age, William Joyce married Hazel Kathleen Barr at Chelsea Register Office on 30 April 1927. The Thirties The period 1933-37 was a hectic time in Joyce's life. During this time, Joyce studied a one year post-graduate course in Philology, and during 1931-3 a psychology course at King's College London. Also during this time period he was a member of Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascist's (BUF) movement. This movement had several clashes with the police. This resulted in Oswald Mosley, William Joyce and two others being tried, and acquitted, before Mr. Justice Branson of taking part in a riotous assembly at Worthing. On 4 July 1934, William Joyce applied and obtained his British Passport. Following the dissolving of his first marriage in 1936, William Joyce married Margaret Cairns White at Kensington Register Office (London) on 13 February 1937; the marriage witnesses being Mrs. Hastings Bonora and John A. Macnab. After becoming disgruntled with Mosley's B.U.F organisation in 1937, Joyce founded his National Socialist League and Margaret Joyce became the League's Assistant Treasurer. In 1938, he extended his British Passport by one year. On 17 November 1938, charges of assault against William Joyce were dismissed by Mr. Paul Bennett at West London Police Court. William Joyce was again in court on 22 May 1939, when charges against him under the Public Order Act were dismissed by Mr. Marshall at Westminster Police Court. Joyce in Germany In July 1939 William Joyce sent a letter to a suspected German agent in the UK. He revealed in the letter that he was planning to travel to Germany. At this time, MI5 had produced a report that recommended that when war with Germany was declared, William Joyce should be detained. In August 1939, just before the outbreak of war, Joyce renewed his British Passport for another year and dissolved his National Socialist League. On 1 September 1939, two days before war was declared, Special Branch detectives went to arrest Joyce at his Earl's Court home. However, they found that William Joyce and his wife had left for Germany on 26 August. Joyce's sister claimed that a MI5 agent had tipped off Joyce that he was about to be arrested. During Late 1939 and early 1940, while his British Passport was still valid, William Joyce made several radio broadcasts in English. Because William Joyce held a British Passport he had a duty of allegiance to the British crown. By broadcasting for the Germans, Joyce broke that allegiance and consequently committed high treason (See my article on the treason and treachery acts for a greater explanation of treason). Shortly after his passport expired, Joyce fell out of favour with the Germans. He continued to make radio broadcasts to the U.K. Joyce's nickname of "Lord Haw Haw" was given him by a correspondent in a Daily Express article: "A gent I'd like to meet is moaning periodically from Zeesen [the site in Germany of the English transmitter]. He speaks English of the haw-haw, damit-get-out-of-my-way variety, and his strong suit is gentlemanly indignation." In was in fact Baillie-Stewart who made the September 1939 radio broadcast which was heard by Jonah Barrington (a pen-name used by a Daily Express correspondent). After hearing this broadcast, Barrington wrote about a gentleman speaking with an English accent of the haw-haw type, get-out-of-my-way type. On 18 September 1939, Barrington wrote for the first time about Lord Haw-Haw. These comments were aimed at Baillie-Stewart 'the Sandhurst-educated officer and gentleman' (who made the broadcast heard by Barrington) and not the nasal-accented William Joyce. It should be remembered that these broadcasts were made at a time of very heavy German air raids. While people regarded the broadcasts as something of a joke, Joyce was regarded as a traitor who would hopefully get what he deserved. William Joyce made radio broadcasts throughout the war, although during his last broadcast he was heavily drunk. He was arrested by British Troops near Flensburg on the Danish-German border. They came across what appear to be a German civilian, whose voice sounded familiar. It eventually dawned who he was. When they challenged Joyce, he put his hand into a pocket. Thinking that he was going for a pistol, the British troops shot Joyce in the leg. Joyce's Arrest After recovering in Lueneberg Military Hospital, William Joyce arrived as a prisoner in the U.K on 16 June 1945. The day before Joyce's arrival, the Treason Act 1945 had been granted Royal Assent by King George VI. William Joyce was charged with three counts of high treason. Due to the need for evidence, concerning the important question of Joyce's nationality, from the U.S.A, the crown court case was put back to September. The Trial On 17 September in the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey, before Mr. Justice Tucker and a jury, William Joyce was charged with three counts of High Treason: 1. William Joyce, on the 18 September 1939, and on numerous other days between 18 September 1939 and 29 May 1945 did aid and assist the enemies of the King by broadcasting to the King's subjects propaganda on behalf of the King's enemies. 2. William Joyce, on 26 September 1940, did aid and comfort the King's enemies by purporting to be naturalised as a German citizen. 3. William Joyce, on 18 September 1939 and on numerous other days between 18 September 1939 and 2 July 1940 did aid and assist the enemies of the King by broadcasting to the King's subjects propaganda on behalf of the King's enemies. The trial lasted three days: 17,18 and 19 September 1945. The main arguments in the case concerned whether the defendant had a duty of allegiance to the King. If there was no duty of allegiance, then Joyce could not be found guilty of treason. William Joyce did not deny carrying out the alleged acts, he just denied that he owed any allegiance to the King. The prosecution accepted that under counts 1 and 2 Joyce did not owe allegiance as he was an American citizen. However, they argued that as he held a British Passport and left the U.K on this passport he had the protection given to passport holders. As protection demands allegiance, Joyce broke this allegiance and committed treason. This point in law was accepted by Mr. Justice Tucker, who ruled that the prosecution's point in law was valid. The judged also directed the jury to find Joyce not guilty of counts 1 and 2. Following the judge's ruling, the jury was left with the question of whether Joyce had made the broadcasts between the dates of 18 September 1939 and 2 July 1940 (the period when Joyce's British Passport was valid). They decided that Joyce had made the broadcasts, and they found him guilty of count 3. As High Treason carried a mandatory capital sentence, the judge sentenced William Joyce to death by hanging. Court of Appeal On 27 September 1945, Joyce's lawyers gave notice of appeal. Due to high treason having only one possible sentence, they could only appeal the conviction not the sentence itself. His lawyers argued that the trial judge was wrong to accept the prosecution's legal arguments relating to the question of allegiance. They argued that the fact the King was unable to offer protection to Joyce in Germany, that Joyce was an American citizen and that Joyce never intended to ask for protection, meant that as no protection was asked for, no allegiance was owed in return. William Joyce's appeal was heard before the Lord Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Humphreys and Mr. Justice Lynskey, on 30 October 1945. On 1 November 1945, they announced that judgement was reserved. On 7 November 1945, it was announced that the appeal was dismissed. In effect, they supported the prosecution argument relating to the protection offered by the British Passport, and the consequent allegiance demanded. House of Lords Due to the important questions of law involved in the case, the Attorney-General granted his certificate on 16 November 1945, which allowed the case to be heard before the House of Lords; the highest British court. The appeal before the House of Lords on 10 to 13 December 1945, was heard by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Macmillan, Lord Wright, Lord Porter and Lord Simonds. This appeal was dismissed, with Lord Porter dissenting, on 18 December 1945. They also announced that they would give their reasons at a later date. The Execution At a few minutes past 9am on 3 January 1946, with a sizeable crowd outside the prison, William Joyce was hanged at Wandsworth Prison in London. After the post-mortem and inquest in the afternoon, William Joyce was buried in unconsecrated ground within the prison grounds (as with all executed prisoners). On 18 August 1976, William Joyce's remains were exhumed and returned for burial in Ireland. Margaret Joyce William Joyce's wife, Margaret, was arrested the same day as Joyce and returned to London's Holloway Prison. It was decided after the war that no further action would be taken against William Joyce's wife Margaret. Although she was born in Manchester, had apparently made no effort to renounce her British Citizenship after arriving with her husband in Germany and made German propaganda radio broadcasts to the UK, no proceedings were taken against her. In documents at the PRO, a MI5 officer admitted that the decision was in effect based on compassionate grounds; namely the trial and execution of her husband. Margaret Joyce died in London during 1972. Source: British Military History 1900 to 1999. William Joyce (Treason) | WWII Forums 07 IX 2023. |

|

|

#10 |

|

Senior Member

Join Date: Nov 2014

Location: UK

Posts: 1,398

|

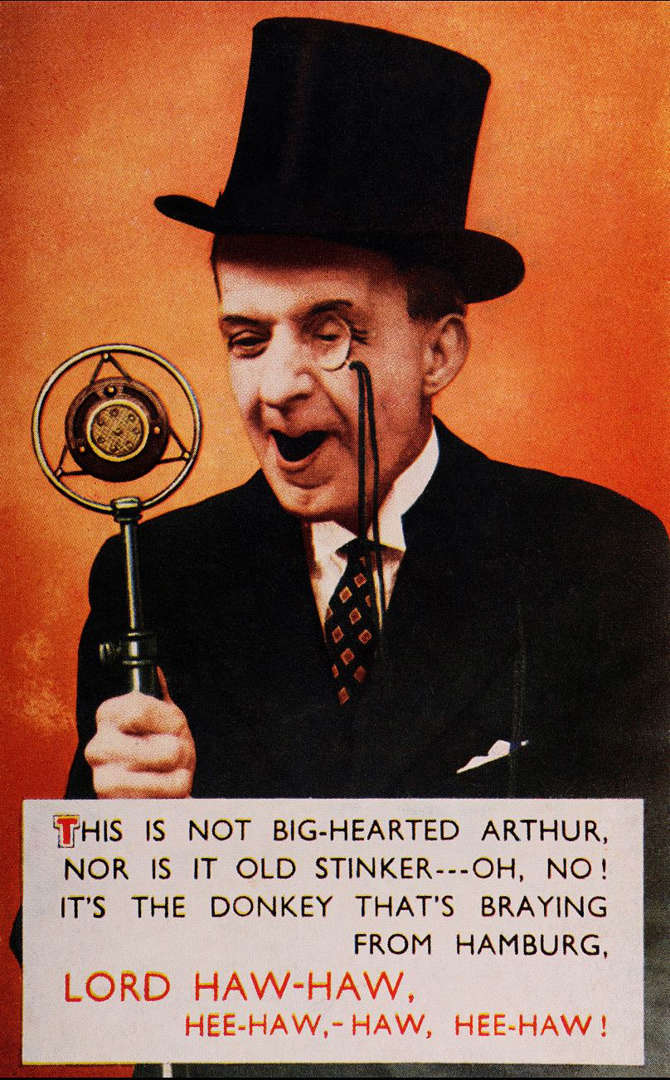

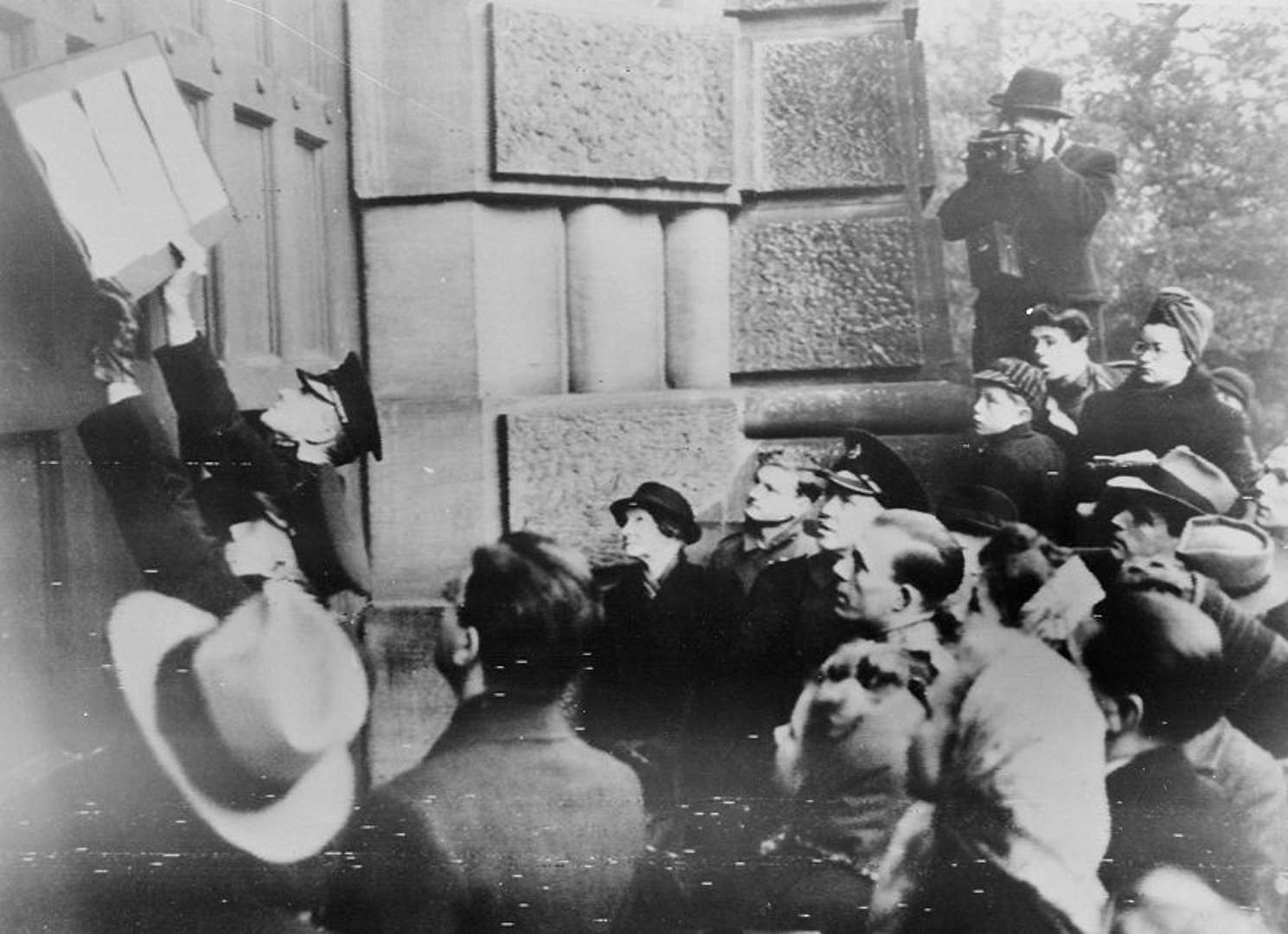

Nazi propagandist Lord Haw-Haw sentenced to death for high treason Story by Saskia O'Donoghue • As one of the most infamous and hated men in Britain, it was perhaps only a matter of time before Lord Haw-Haw got his comeuppance. On 19 September 1945, the notorious Nazi propagandist was given the death sentence after being found guilty of high treason. Born as William Joyce in 1906, the Anglo-Irish broadcaster is ultimately remembered as having betrayed his country during the Second World War. Moving from his birthplace of New York to Galway as a young child, Joyce was recruited in 1921 by the British Army during the Irish War of Independence. Early on, he was suspected of being involved in a murder as well as being a possible informant for the Black and Tans. As a result, he was moved to the Worcestershire Regiment in England but was soon discharged after being discovered to be underage. Returning to school and then enrolling at Birkbeck College in London, Joyce became entranced with fascism and got heavily involved in right wing politics. Following his stewardship of a meeting for Conservative party candidate Jack Lazarus, Joyce was slashed across the face, apparently by communists, which left a permanent scar from his earlobe to the corner of his mouth. The incident was said to have cemented Joyce’s hatred of communism and his dedication to the fascist movement. After the attack, he joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in 1932, immediately distinguishing himself as a talented orator.  In this undated picture, Joyce shows his infamous facial scar He was an active figure until Mosley sacked him following the 1937 London County Council elections. Joyce immediately founded his own organisation - the National Socialist League (NSL). Significantly more anti-Semitic than the BUF, the NSL’s aim was to integrate German Nazism into British society in an attempt to create a new form of British fascism. As war broke out in 1939, though, Joyce fled to Germany with his wife Margaret.After initially struggling to find work in Berlin, he quickly got recruited by Joseph Goebbels’ Reich Ministry of Propaganda and was given his own radio show ‘Germany Calling’. Goebbels, the chief propagandist for the Nazi Party and Minister of Propaganda, was in need of foreign fascists to spread Nazi propaganda to Allied countries - and Joyce was the ideal candidate. His broadcasts tried to increase distrust amongst the British people about their government and claimed that the British working class were being oppressed by the middle classes and Jewish businessmen, who allegedly controlled government ministers.  Joyce pictured at the height of his infamy c.1942 The birth of ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ In Britain, listening to ‘Germany Calling’ was discouraged but not illegal. It was a popular broadcast, with an estimated six million regular and 18 million occasional listeners by 1940. Information was strictly censored by the British government during wartime, so many civilian listeners tuned in to see what was being said by the enemy. Joyce’s dramatic and fiery delivery was considered to be far more entertaining than the sombre, rather dull programming offered by the BBC. In September 1939, Daily Express radio critic Jonah Barrington described Joyce as "moaning periodically from Zeesen [a wartime facility for longwave broadcasting]" who "speaks English of the haw-haw, damit-get-out-of-my-way variety". A vintage postcard featuring a generic Lord Haw-Haw - , the nickname of several announcers of the English language propaganda radio programme Germany Calling  While the moniker was given to several British announcers on Nazi radio, Barrington gave Joyce the nickname 'Lord Haw-Haw' - and it stuck. By 1941, Joyce himself began to trade on the notoriety of the nickname and he began to introduce himself as "William Joyce, otherwise known as Lord Haw-Haw". Throughout the war, his propaganda-heavy broadcast became even more concerning and British authorities and citizens alike came to see the radio shows as part of increasingly legitimate threats to Britain and its Allies. Joyce recorded his final broadcast on 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Berlin rage and Germany were losing the war. Thought to be drunk, he blamed the UK for taking the war “too far” against Germany and warned about the apparent “menace” of the Soviet Union. Joyce signed off with a final defiant, "Heil Hitler and farewell”. Lord Haw Haw, unseen, arrives at the Old Bailey in London, for his trial for treason in 1945  A month later, on 28 May, Joyce was captured by British forces at Flensburg, near the German border with Denmark - the last capital of the Third Reich. He was transported to England and put on trial at the Old Bailey on three counts of high treason. Lawyers argued that he was not a real British citizen, having been born in the United States but that point was refuted, with prosecution saying he had briefly been in possession of a British passport.  A notice board for the execution of William Joyce aka Lord Haw Haw outside Wandsworth Prison on the eve of his execution for treason, January 1946. In the end, the court concluded that he had betrayed his country and therefore had committed high treason. After the guilty verdict, Joyce was taken to Wandsworth Prison and was hanged on 3 January 1946 at age 39. He was the penultimate person to be hanged for a crime other than murder in the UK. The last was Theodore Schurch, who was executed for treachery the following day at nearby Pentonville Prison.  A throng gathers outside Wandsworth Prison to witness the posting of an announcement of the execution by hanging of William Joyce At the gallows, Joyce was unrepentant. He is alleged to have said: “In death as in life, I defy the Jews who caused this last war, and I defy the power of darkness which they represent. I warn the British people against the crushing imperialism of the Soviet Union. May Britain be great once again and in the hour of the greatest danger in the West may the standard be raised from the dust, crowned with the words – 'You have conquered nevertheless'." Lord Haw-Haw sentenced to death for high treason |

|

| Tags |

| british fascism, fascist martyr, irish/american, opposed jewry |

| Share |

«

Previous Thread

|

Next Thread

»

| Thread | |

| Display Modes | |

|

|

All times are GMT -5. The time now is 11:57 PM.

Page generated in 0.15818 seconds.

Linear Mode

Linear Mode